On World Autism Day, a well-intentioned opinion piece was published titled “Autistic People Are Empathic Too.” Written by a Flemish psychotherapist, the article set out to dismantle the persistent stereotype that autistic people are cold, distant, or even dangerous. At first glance, it seemed like a necessary and courageous corrective.

But as an autistic adult with a background in social work and years of lived and shared experience within the autistic community, I read it with growing frustration. Despite the good intentions, the article ends up reinforcing the very logic of the prejudice it aims to undo.

Let’s start with the framing. Why should anyone — autistic or not — have to prove that autistic people are capable of empathy? If we begin from that premise, we implicitly accept that empathy is the measure of human worth. And that unless we justify ourselves, we are suspect — less than human. That’s not a step toward liberation; it’s compliance with a system that never fully accepts us as equals.

The article then goes a step further: not only are autistic people empathic, it argues — we’re more empathic. We’re supposedly hypersensitive to emotions, equipped with stronger moral compasses, and naturally inclined to act for the greater good. But this, too, is a caricature. The emotionless robot is simply replaced by the moral saint. Once again, we are symbolized rather than seen. Those who don’t fit the mold — those who aren’t overflowing with empathy or who remain socially awkward — are excluded all over again. It’s the kind of thinking echoed by certain strands of “autistic supremacy” ideology, and it’s no less harmful.

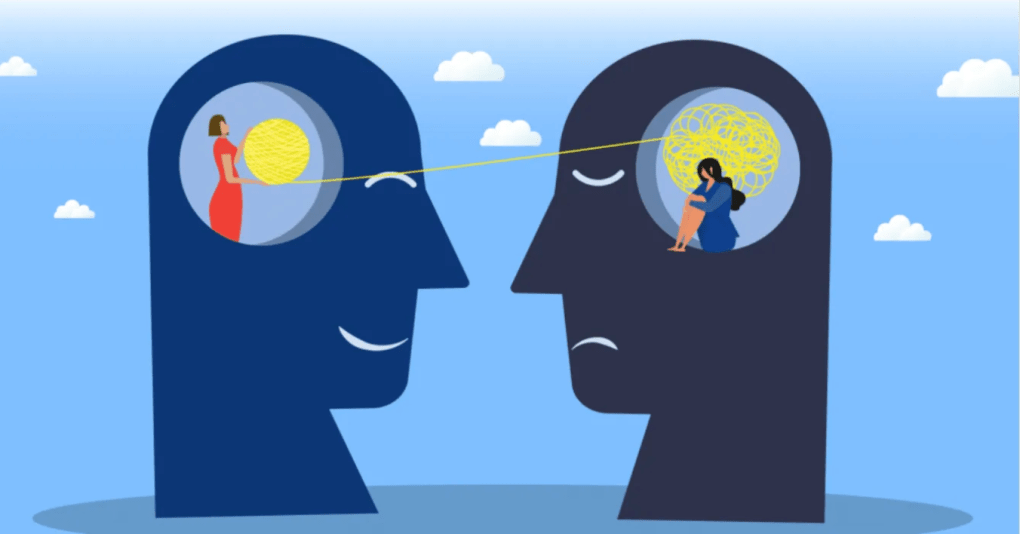

Another troubling notion: the claim that “distant” autistic behavior must stem from trauma. As if the only legitimate reason to differ from neurotypical norms is if we’re wounded. As if our behaviors require excuses instead of recognition. What if we express care in ways that are unusual or hard to translate? What if closeness feels different to us, or comes in forms we don’t yet have the words for? What if our silences, hesitations, or tangents aren’t masks for hidden empathy but genuine parts of who we are?

The author’s invocation of the “double empathy problem” doesn’t help either. This theory, proposed by a British autistic academic, suggests that communication breakdowns between autistic and non-autistic people are mutual. While often celebrated, the theory glosses over real power imbalances, lacks empirical clarity, and is of limited practical use. It flattens the immense diversity within the autistic community, assumes moral equivalence, and ignores structural inequality. Citing it as evidence of our empathy is ironic at best.

The piece also makes a persistent effort to reinterpret autistic communication through mainstream social norms. Behaviors like “leaving someone alone” or “talking about yourself” are reframed as secret forms of empathy. But not all misunderstandings are warm at heart. We are not encoded versions of non-autistic people. We are people who are autistic.

Perhaps most concerning is what’s left unsaid. Autistic individuals with multiple disabilities, those who communicate nonverbally or struggle with emotional reciprocity, are often erased from these narratives. Writers who claim to speak for us frequently forget large parts of the spectrum and use the least threatening language possible. But representation should not be a PR campaign. It shouldn’t be about fighting stereotypes with softer stereotypes. We need complexity. We need truth.

The article ends with a familiar, polished tone: “I’m always open to honest and sincere conversation.” That may sound admirable, but for many autistic people, that’s exactly the exhausting thing. It reflects deep social masking, emotional suppression, and the pressure to remain palatable. It is not unreasonable for autistic people to be angry. To be direct. To feel weary of constantly having to explain ourselves. That, too, is human.

In short: autistic people don’t need to prove they’re empathic. Especially not through a collective “we” that leaves many of us out. Some of us don’t display empathy in conventional ways. Some of us feel deeply but can’t show it. Some might not feel it at all, at least not at certain moments. And that doesn’t make us less human.

If anything needs to be proven, it’s this: nothing human is alien to us.

That’s a better starting point for the next article.