On music for me as not only mirror of the autistic self, but a vital tool for survival, rejecting stereotypes and medicalization

More than any other sensory input, sound dictates the quality of my life. When it’s noise, it inflicts a stress more profound than an overwhelming smell, a piercing light, or a void of taste or touch. But when sound becomes music, it transforms. It gives me the impetus to create something beautiful, to look up at the world again, and to move forward.

This relationship with sound is something I’ve pondered for years, a reflection deepened by the many messages I’ve received over the years. People from across the globe share their own musical experiences with autism, and the diversity within their stories never ceases to amaze me. When I read newspapers or watch mainstream media, I rarely recognize myself. But in the lived experiences of other autistic people, in their intimate accounts of music and sound, I find a profound, validating recognition.

Jazz, Math, and Other Myths

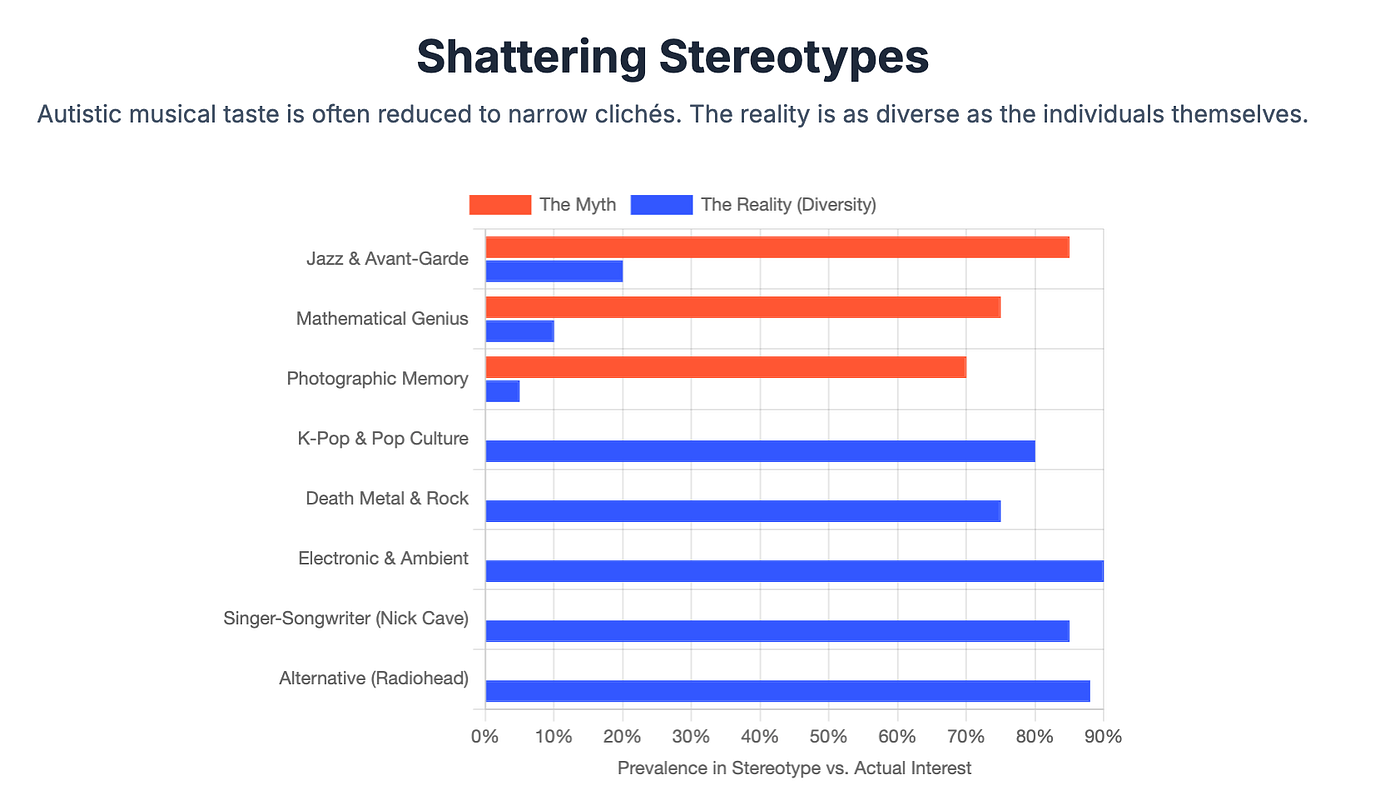

There’s a persistent stereotype that autistic people gravitate towards jazz and avant-garde classical music. The theory goes that our supposed “extreme systematic thinking” draws us to compositions rich in patterns, complex execution, and intricate harmonies. Apart from a little jazz, that’s not really my cup of tea.

I’m reminded of this whenever someone asks about my musical tastes. It feels just like being asked if I’m a mathematical genius or have a photographic memory. These are clichés I still encounter after all these years. In my first Dutch book, Autistisch gelukkig (Autistically Happy), I emphasize that autism is different for everyone, and this is unequivocally true for our connection to music.

What I’ve learned from others in the autistic community is that our musical preferences are as varied as we are. I know autistic people who listen exclusively to K-pop, others who swear by death metal, and some who dedicate their lives to cataloging every known recording of a single Chopin nocturne. Me? I can lose myself completely in the raw, narrative depths of Nick Cave, the atmospheric alienation of Radiohead, or even in certain electronic music that my wife lovingly refers to as “just noise.”

The Mirror of the Self

It’s not that we don’t listen to music for emotional reasons; we absolutely do. But the nature of that connection often differs from the neurotypical experience. Where I find common ground with researchers is in the observation that we often seek music that mirrors our internal state, rather than music that aims to change it.

In music, I recognize myself. I find a reflection more accurate than in conversations, more honest than in books, and certainly more real than in television series where autistic characters are often portrayed so stereotypically I wonder if the creators ever actually spoke to an autistic person. As I once said in an interview, the portrayal of autism in fiction often feels like a display of something exotic.

Music, however, is different. It only truly moves me when I see a facet of myself in it. Each time, a good piece of music introduces me to another corner of my own being. It’s a direct experience. The moment the celebrity of the musician or the reputation of the composer overshadows the music itself, its effect on me diminishes.

I remember sessions with a music therapist when I was younger. I’m not talking about the forced “therapeutic” lessons where songs were weaponized to teach me social skills — I hated those with a passion. I mean the sessions where we simply made music together. No words, no learning objectives. In those moments, I could “say” things I could never have captured in language.

The Therapeutic Straitjacket

Music is often framed as a therapeutic tool for autistic people, a perspective I hold mixed feelings about. As I often state in my lectures: not everything an autistic person does needs to have a therapeutic goal. When I play the piano, it’s supposedly good for my “executive functions.” When I dance, I’m working on my “motor planning.” Sometimes I just want to shout: Can’t I just enjoy music because it’s beautiful?

This is a specific kind of pressure I know all too well. I experienced it countless times at school, where a song I loved would be played during a moment of “reflection.” Afterwards, I could no longer stand it. It wasn’t just that it was misinterpreted; the act of explaining, of dissecting it, was enough to kill it.

This connects to a theme I explore in my book Gedurfde vragen (Bold Questions): the tendency to medicalize every aspect of an autistic person’s life. It’s a form of patronizing that feels deeply familiar. We are often seen not as people living, but as patients being treated. We can’t just have hobbies; we must have interventions.

Daily Survival with Sound

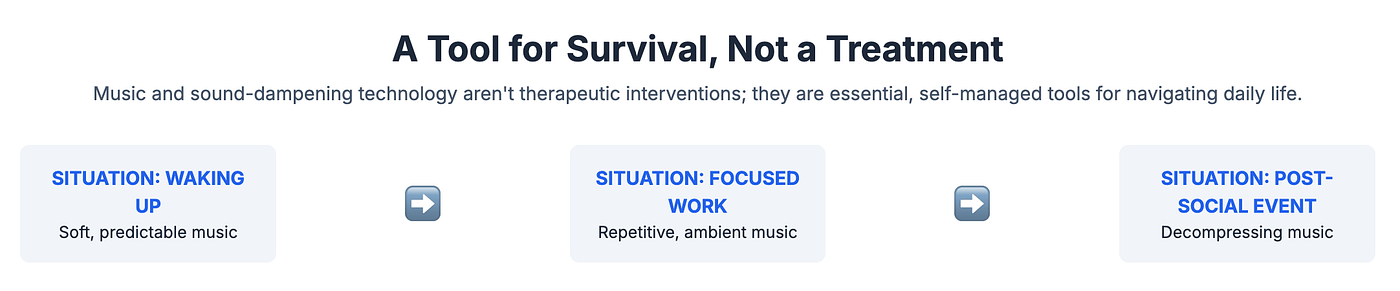

Living with autism means a constant negotiation with the sonic world. I’ve developed strategies, not because a therapist prescribed them, but out of necessity.

My day starts softly, with music that is predictable, giving my brain time to wake up. While writing, I listen to repetitive, ambient music that creates a sonic cocoon, allowing me to focus. After a demanding social event, like a lecture, I need music that helps me decompress and re-center.

Some might call this my “portable therapist,” but it feels more like a prosthesis. Just as someone with poor eyesight wears glasses to navigate the world, I use music and my noise-cancelling headphones to make the world bearable. They are not a luxury; they are a necessity. They are what allow me to attend book fairs, give presentations, and participate in a life that would otherwise be overwhelming.

The Intense Connection of Making Music Together

The most intense musical experience for me is found in creating it with others. An autistic woman once described it perfectly as “a feeling of warmth, of joy and despair, of harmony and togetherness. As if you can finally breathe again.”

I recognize that feeling completely. When I make music with others, the crushing weight of social expectation lifts. We don’t need to maintain eye contact or decipher unspoken social codes. We are simply together in the music. It’s one of the few situations where I feel truly connected to other people without it draining my energy.

Researchers are now catching up to what we’ve known for a long time, observing that making music together facilitates ‘interpersonal synchrony’ and provides a structured, safe framework for social interaction to emerge naturally.

A World of Difference

As I write this, I think of all the emails I still receive. People who have just received their diagnosis and feel lost. People struggling with the daily friction of being autistic in a neurotypical world. People looking for permission to be themselves.

For them, and for me, music is often an answer. Not as a therapy or a cure, but as a way of being. A way to breathe. A way to live.

Music is a mirror in which I recognize myself, but it’s also more. It is a language when words fail. An anchor when the world becomes a storm. A joy that requires no justification. It is a way to be myself in a world that often asks me to be someone else.

And sometimes, when the right notes hit at the right moment — when Nick Cave sings of his own search for meaning, when Radiohead perfectly articulates alienation without a single word — music is simply beautiful. Devoid of therapeutic purpose, free from deeper meaning, and without any need for explanation.

That, I believe, is the core of it. Autism doesn’t have to be a limitation, but simply a different way of being. And music, in all its forms, is a perfect expression of that truth. We may hear differently, feel more intensely, and need things others don’t. But the beauty we experience is just as real and just as valuable. Perhaps even more so, because we know, intimately, what it’s like to live without it.