HSP isn’t ‘Autism-Light’. HSP is deep, spontaneous intuition (high context). Autism is reasoned logic (low context). Different wiring, different support.

In our hyper-connected world, more people than ever are searching for a framework to understand their differently-wired brains. The neurodiversity movement has brought terms like Autism and ADHD into the mainstream, and in this quest for self-knowledge, the term “Highly Sensitive Person” (HSP) has exploded.

It’s a good thing, this search for self-understanding. But there’s a significant danger lurking in this sea of good intentions. Online, and in popular conversation, the lines between High Sensitivity and Autism are blurring. They are lumped together, or worse, HSP is treated as “Autism-Light,” and autism is dismissed as an extreme form of sensitivity.

This confusion isn’t just factually incorrect; it’s harmful. As a recent communiqué from experts like Esther Bergsma (author of The Brain of the High Sensitive Person), Séverine Van De Voorde (high sensitivity expert) and Peter Vermeulen (author of Autism and the Predictive Brain) painfully clarifies, confusing the two means risking the wrong kind of support. And the right support is everything.

The Great Imposter: Why We Mistake Stress for a Trait

Here is the core of the confusion: we try to distinguish autism and high sensitivity based on behaviors caused by stress. And that is the wrong metric.

Both autistic individuals and HSPs often have a stress system that activates more quickly, more frequently, and more intensely than average. Why? Because both groups are operating with a brain that deviates from the “standard” society is built for.

This constant friction leads to an overloaded system. And what are the symptoms of an overloaded stress system? Sensory overload, irritability, overreactivity, emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, cognitive difficulties, and physical complaints.

These symptoms, which many associate with autism, are often the consequence of chronic stress, not the core trait itself. An HSP and an autistic person can both be overwhelmed in a noisy supermarket, but for different reasons.

The HSP may be overloaded by the meaning — the frantic energy of other shoppers, the emotional state of the cashier, the 50 types of mustard they feel compelled to analyze for the “optimal choice.” The autistic person may be overloaded by the raw data — the flickering fluorescent lights, the conflicting sounds of beeps and music, the unbearable proximity of other people’s bodies.

This extends to perceived strengths, like an ‘eye for detail.’ In an HSP, this is a context-connecting skill, seeing how details form a whole. In autism, it is often an eye for detail changes or specific, focused facts, which may or may not be relevant to the overall social context.

The Core of High Sensitivity: It’s Not Sensitivity, It’s Depth

The most common mistake is reducing high sensitivity to simply “being sensitive to stimuli.” That is a side effect, not the cause. The scientific core of high sensitivity is depth of processing.

A highly sensitive brain processes information more complexly and thoroughly. It notices subtle details in the (social) context with great clarity and rapidly connects them into a big picture. Where a non-HSP brain might see a situation and react, the HSP brain activates a “pause-to-check” system. It files new information against existing insights and weighs them against a strong “optimal-option ambition” — a drive to find the very best action to take. This is often heavily influenced by its highly active social brain regions, which weigh the needs of others.

This manifests as a crucial characteristic: an above-average context sensitivity.

The Core of Autism: A World Without Context

And here, we find the most fundamental opposite of high sensitivity. Autism, according to the formal DSM-5 criteria, is characterized by persistent difficulties in social communication and interaction, and by restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities.

When we dig deeper, we see that many of these challenges stem from what Peter Vermeulen calls “context blindness.” The communiqué refers to it as a below-average context sensitivity.

Autistic people naturally struggle to use context spontaneously, unconsciously, and quickly to understand and predict the world. Where the HSP brain breathes in context, the autistic brain must reason it.

Here’s a practical example: A manager tells an employee, “This report is great.” The HSP employee hears the words, but senses the manager’s slight hesitation and sees their micro-expression of worry. The HSP knows this contextually means, “This is a good start, but I have concerns about the data on page 3.”

The autistic employee hears “This report is great.” They file it as a completed and successful task. They have missed the implied, unstated (contextual) request for changes, not from a lack of care, but because their brain processes the words as absolute data.

The Empathy Paradox: Spontaneous Knowing vs. Deliberate Reasoning

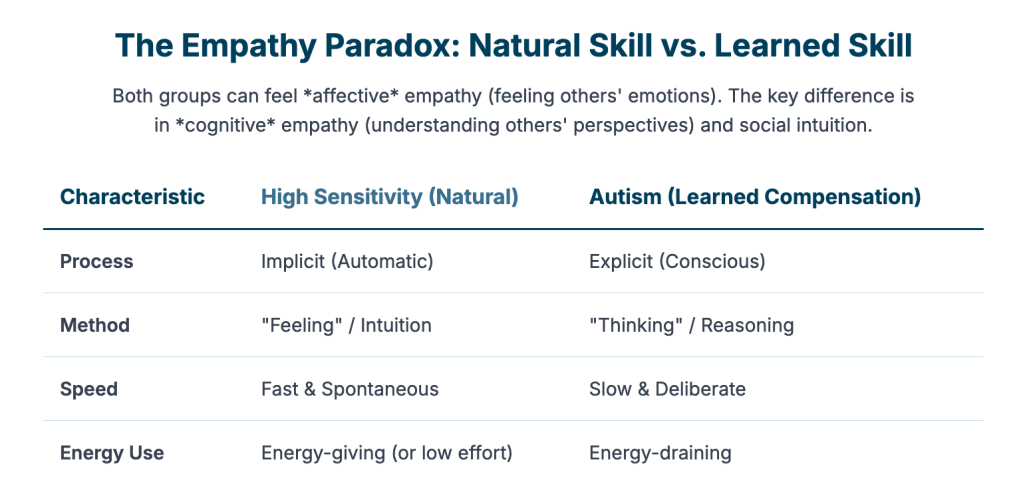

Nowhere is the difference clearer than with empathy. We must distinguish between two types. Affective empathy is feeling another’s emotions, and both groups can be strong in this, often to the point of being overwhelmed.

The difference is cognitive empathy: understanding another’s thoughts, feelings, and perspective.

In high sensitivity, we see a highly developed spontaneous cognitive empathy. It’s a natural, implicit, and effortless process. An HSP “knows” or “feels” intuitively what is going on with someone else and what is needed in a social interaction. They read between the lines as their first language.

In autism, these fast, unconscious social-cognitive processes are naturally less developed. However, autistic people (especially those with average or high intelligence) can compensate. They develop a reasoned** cognitive empathy**. They learn through observation and logic what is expected of them. They create “social scripts.”

Let’s take another example: A colleague, Jane, is sighing and staring blankly at her computer.

The HSP walks past, and the “vibe” hits them like a wave. The set of Jane’s shoulders, the rhythm of her sigh, the tension in her fingers — it all combines spontaneously into the insight: “She’s not mad, she’s deeply frustrated and feels unsupported.” The HSP intuitively knows whether to offer a quiet cup of tea or just give her space.

The autistic person walks past and notices the sigh (a piece of data). This triggers a reasoned process: “1. Jane is sighing. 2. Sighing is in my mental script for ‘unhappy.’ 3. The social rule when someone is unhappy is to ask, ‘Are you okay?’” They perform the action, but it’s a conscious, logical deduction, not an intuitive knowing. If Jane’s response is off-script, it can be confusing and draining.

This is the crucial difference:

Naturally strong skills are implicit, spontaneous, and fast. They give energy (or cost no effort). Learned skills are explicit, reasoned, and slow (though they get faster with practice). They cost enormous energy.

An HSP might leave a party overwhelmed by the depth of all the information they perceived. An autistic person often leaves that same party exhausted from the mental effort of constantly having to decode and reason through that exact same information.

The “Bird and the Egg” Fallacy

The communiqué uses a perfect logical analogy. “If it’s a bird, it lays eggs.” This is true. But the reverse (“It lays eggs, so it must be a bird”) is a well-known fallacy. Reptiles and fish also lay eggs, but that doesn’t make them birds.

It’s the same with this. With autism, we often see sensory overload. But just because you experience sensory overload doesn’t automatically mean you have autism. Overload is the “egg.” Autism, high sensitivity, ADHD, burnout, or even a concussion can lay that “egg.”

A Critical Reflection: Why “Acceptance” Isn’t Enough

It’s worth pausing here to reflect on our current moment. The broad neurodiversity movement, while well-intentioned in its push for acceptance, has had an unintended side effect: it has made these precise, clinical distinctions seem unimportant, or even offensive. In a pop-culture rush to destigmatize, “autism” can become a catch-all for any social awkwardness or sensitivity.

This communiqué serves as a vital, professional course correction. It re-injects the necessity of clinical psychology into a conversation that was becoming dominated by social identity. It reminds us that these are not just different ‘flavors’ of thinking; they are fundamentally different neurological operating systems. This isn’t about gatekeeping a label; it’s about preventing harm. Precision in diagnosis is the only path to effective support.

Why This Distinction is a Lifeline

A label isn’t an endpoint; it’s a signpost. But if the signpost points you in the wrong direction, you end up further from home than ever.

The support an HSP needs is fundamentally different from what an autistic person needs. An HSP benefits from learning to manage the depth of their processing and setting boundaries for their powerful social intuition.

An autistic person benefits from support that makes the world predictable and makes the context explicit. They need to manage an energy battery that drains from reasoning their way through the world.

If an HSP is misdiagnosed as autistic, they may be offered social skills training to “practice 3 seconds of eye contact.” This is pointless. The HSP is already tracking ten non-verbal cues at once; they don’t need more social data, they need permission to disengage from it.

If an autistic person is mislabeled as HSP, they may be told to “trust their intuition” and “feel the vibe of the room.” This is like telling someone to “just see the color red” when they’re colorblind. It’s not a faculty they can “just use,” and the advice is frustrating and invalidating.

In the search for who we are, the wrong answer is more dangerous than no answer at all. Leave the diagnosis to professionals who look beyond the symptoms of stress and have the courage to examine the fundamental wiring underneath.

Source: You can download the communiqué in English on the website of Autism in Context in pdf or click on this link.